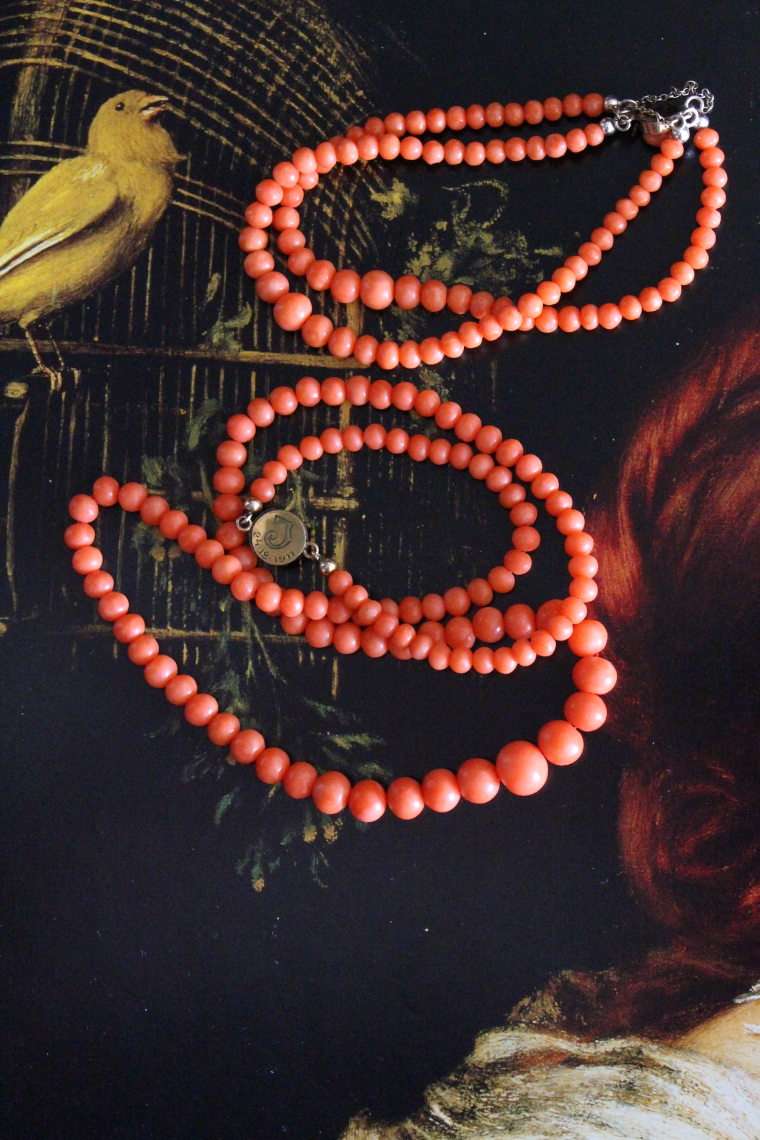

My newest jewellery acquisition is a set of beaded coral, a necklace and a bracelet, here pictured draped across Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Venetian pastiche Fair Rosamund (1861). The model, Fanny Cornforth, wears a coral necklace which Rossetti borrowed from Georgiana Burne-Jones while working on the portrait. Although coral has been popular since antiquity, I particularly associate these beaded necklaces with the Pre-Raphaelites, as they are featured in so much of their work.

My newest jewellery acquisition is a set of beaded coral, a necklace and a bracelet, here pictured draped across Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Venetian pastiche Fair Rosamund (1861). The model, Fanny Cornforth, wears a coral necklace which Rossetti borrowed from Georgiana Burne-Jones while working on the portrait. Although coral has been popular since antiquity, I particularly associate these beaded necklaces with the Pre-Raphaelites, as they are featured in so much of their work.

Coral was for a long time perceived as something ambiguous and difficult. It was harvested from the sea, but no one knew exactly where it came from and its origins were shrouded in terrifying myths. According to Greek mythology coral was created when Perseus beheaded Medusa on the shores of the Red Sea, and when he placed the severed head on a pile of seaweed, the pile was petrified by the blood seeping from it, or alternatively the seaweed began to absorb Medusa’s powers and turned into coral.

Coral was for a long time perceived as something ambiguous and difficult. It was harvested from the sea, but no one knew exactly where it came from and its origins were shrouded in terrifying myths. According to Greek mythology coral was created when Perseus beheaded Medusa on the shores of the Red Sea, and when he placed the severed head on a pile of seaweed, the pile was petrified by the blood seeping from it, or alternatively the seaweed began to absorb Medusa’s powers and turned into coral.

Coral has been worn for protection against evil since the antiquity, yet it has always confused naturalists and collectors. It is both natural and artificial, both an animal and a mineral, and it proved notoriously difficult to classify alongside other marine invertebrates such as molluscs and jellyfish. Today we know that coral belongs to both the mineral, vegetal and animal kingdoms and that it is a living organism which feeds, reproduces and lives in colonies. In fact, the coral reefs are entire ecosystems in themselves as they feed and shelter other organisms such as sponges and fish.

Coral has been admired for its vibrant colour, displayed in cabinets of curiosities, been widely used in jewellery, rosaries and even to decorate weapons. It has also played a central role in religious art, symbolising for instance the tree of life, the blood of Christ and the resurrection. Coral was also believed to carry sacred and medicinal qualities and today components of coral reefs are used in chemotherapy drugs to fight cancer. As a material coral is capable of being both beautiful and ugly, depending on whether it is polished or left in its natural state, and in her article for Victorian Review, Katharine Anderson suggests that it therefore appealed not only to those who favoured it for personal adornment, but also to naturalists drawn to it in its natural, grotesque form. [1]

As coral was known for its protective qualities, it was often gifted to children and infants, a custom which dates back to ancient Rome. In her book on the cultural history of jewellery, Brilliant Effects, Marcia Pointon draws attention to the fact that in the 17th and 18th centuries coral was used in children’s toys such as rattles and whistles “to make safe this puzzling and difficult to classify substance” by connecting it with the innocence of childhood. [2]

In the early 19th century, Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign (1798-1801) led to a rise of the Egyptian Revival style in decorative arts, jewellery and architecture. It became fashionable to wear jewellery inspired by antiquity, such as strings of cameos and micromosaics, depicting mythological figures and archeological discoveries. Coral jewellery gained popularity and was worn as parts of great sets, comprised of necklaces, bracelets, earrings, brooches, combs and tiaras.

Where the late 18th and early 19th century had been seized by a craze for archeology and antiquity, the Victorian era was characterised by the interest in natural history, which brought on an obsession with jewellery inspired by shapes found in nature. Coral became even more popular in the Victorian era and was widely used as a material in conventional jewellery, often carved into cameos and elaborate naturalistic motivs, such as flowers, leaves and clusters of berries.

One aspect of coral which I find fascinating is explored by Pointon in Brilliant Effects, where she analyses Ariel’s song from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, emphasising how the human body after death is turned into the materials it coveted in life: precious coral and iridescent pearls; “Full fathom five thy father lies,” Ariel sings; “Of his bones are coral made; / Those are pearls that were his eyes; / Nothing of him that doth fade, / But doth suffer a sea-change / Into something rich and strange.” [3]

Coral is harvested from the sea to decorate the human body, but unlike the body coral does not decay, for when it is removed from its natural surroundings it turns from a living organism to a hardened mineral, enabling it to outlive its wearer. In The Tempest nature is unequivocally triumphant as coral and pearls grow on the drowned man, adorning the body even in death.

How grotesque my set of coral jewellery suddenly feels! Made in the early 20th century it would have been a product of the revival of the style of the early 1800s, itself a revival of ancient styles of jewellery. Still, it would have been far removed from ancient myths and superstitions and worn as a fashionable accessory rather than an amulet intending to ward off the evil eye, and in all probability it would not have given its wearer a headache from pondering how to classify it. This set dates from the 1910s and although it has been restrung and parts of the lock has been replaced at some point, the personal inscription remains intact: J, 24.12.1911. Perhaps it was a Christmas gift?

Lastly, here are some examples of coral objects and jewellery, depicted in art or as they appear in museums and private collections. Here coral does not appear in its natural state, it has been removed from the sea and partly or entirely altered, reborn as elaborate jewellery or hybrid objects.

Click on the individual images for full size and descriptions.

Reading

Katharine Anderson, ‘Coral Jewellery’, Victorian Review Vol. 34, No. 1 (Spring 2008)

Joan Evans, A History of Jewellery, 1100-1870

Marcia Pointon, Brilliant Effects: A Cultural History of Gemstones & Jewellery

Natural History Museum London, Highlighting coral reefs at risk